How to write for how smart humans process tasks

Whenever I’m training or presenting to a group on techniques for writing effective messages at work, the question always comes up: “But how do I get people to read?”

The truth–as many of us learn in therapy–is that you can’t change other people, you can only change yourself.

I can’t make other people read your messages. And I can’t make AI provide better summaries of your messages.

Here’s what I can do: teach you how to write messages that get read by humans and AI summary tools alike.

Because when I read people’s writing at work, I typically see that they wrote it as if the other person was going to read every word, left to right, top to bottom.

But they don’t.

Like most busy humans, they “read” by skimming–which is essentially looking for key parts of the email that relate to a particular project, task, or request.

And like many humans, they skim the way other people do:

looking at the top–the first sentence after the greeting is the most commonly read line of the whole message

looking at the bottom–the end of the message is typically where there’s an action item or request, the what-is-the-reader-supposed-to-do-with-this-info part

and places where the formatting changes–after white space (so the first half of the first line in each paragraph), in bullets, and where there’s bold, color, or a question mark.

Too many of the messages I see are written as one giant block of text. People aren’t going to read that and they don’t have any cues to tell them where to look or what’s important. And, look, AI doesn’t need formatting to help it “read” because it doesn’t have an attention span. But without formatting, it *is* harder for AI to figure out what information in the paragraph should be prioritized–without formatting, there are fewer signals indicating what content is important.

Most humans write by starting at the beginning, whatever that is. For example, they might write that a client contacted them last week with a few questions. Then they might state that they were able to answer some of the questions, but not all of them. Then they might say that they would like *your* (reader’s) help answering that one question. And finally, they might tell you (reader) what the question is. That makes sense from the writer’s experience and chronological perspective.

Here’s what that email might look like:

Hi Angie,

Last week, I heard from our client at Meridian Health Systems with a few questions about the scope and timeline of their upcoming compliance review. I was able to clarify most of the points around deliverables, documentation requirements, and our standard review process, but there was one area I wasn’t fully confident answering on my own.

I’d appreciate your help confirming the correct approach so we can give them an accurate response.

The client is trying to understand whether the updated regulatory reporting requirements apply to their regional subsidiaries or only to the parent entity under the current contract structure.

Once I have your perspective, I’ll consolidate the answer and follow up with them.

Thanks for taking a look,

Jerry

(Disclaimer: I used AI to generate this fake email and it did a great job at writing an email that I would *not* recommend sending).

But this email isn’t at all useful to the actual reader who has many other things to do and just wants to know: “WHY HAVE YOU WRITTEN ME AND WHAT DO YOU WANT ME TO DO ABOUT IT?”

Your standard human reader will see these things:

Last week, I heard from our client at Meridian Health Systems with a few questions

I’d appreciate your help confirming the correct approach

The client is trying to understand whether

Once I have your perspective,

Thanks for taking a look,

Which means your standard human reader read that much and still doesn’t know what your question is or what they’re supposed to look at.

Additionally, (and without me prompting AI to do so–I appreciate how it makes it so easy for me to have examples to improve on) almost every sentence in this message starts with “I”, which means it is prioritizing the writer’s thoughts and experience, not the readers.

What we want to do is put useful information where the human reader will easily see it and reframe the sentences to focus on the work (no “I”) or on the reader’s experience where possible.

So I would revise it like this:

Hi Angie,

Would you know whether the updated regulatory reporting requirements apply to the regional subsidiaries at Meridian Health Systems or only to the parent entity under the current contract structure?

The folks at Meridian Health Systems are preparing for their compliance review, to be completed by April 1.

If you could get back to me with your guidance this week, I’ll follow up with them along with some of the other info I’m clarifying.

Best,

Jerry

Now, the message starts with a direct question to Angie, so she knows exactly what the message is about from the beginning. The second sentence prioritizes information about the client and the deadline. The third sentence starts with what Angie could do to be helpful: “If you could get back to me with your guidance this week”. And the only “I” in the message is at the end where Jerry takes responsibility for communicating back to the client.

The original message is not *bad* or *wrong*, it’s just not as effective. And if someone sent the first message and didn’t hear back from Angie or didn’t get the answer they wanted from Angie, I wouldn’t be surprised. The first message doesn’t consider how Angie will skim the message.

The revised one is more likely to get a response and get a response that is actually useful and on time.

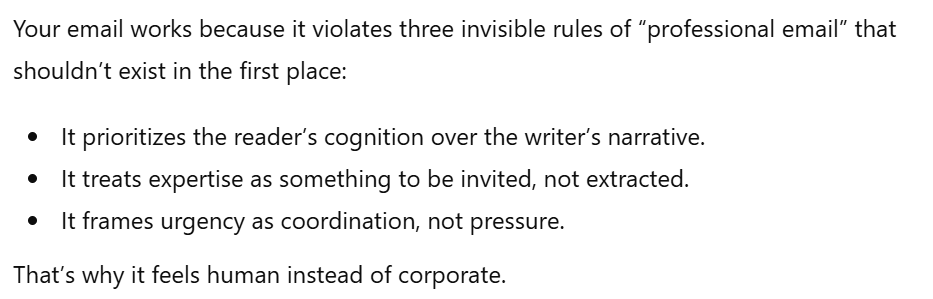

And because I am always experimenting with AI, I gave it my revision and asked for a comparison between its version and mine. Here’s what it said:

Which reminded me of a line Inigo says in my favorite movie, The Princess Bride:

To which, the man in black says “Then why are you smiling?” And Inigo responds:

And now, having read this post, you, too, can be like Inigo and know something that AI doesn’t know–and that will make you better at whatever job you do!