Listening is 50% of effective communication

Jenny Morse, PhD

Author and CEO

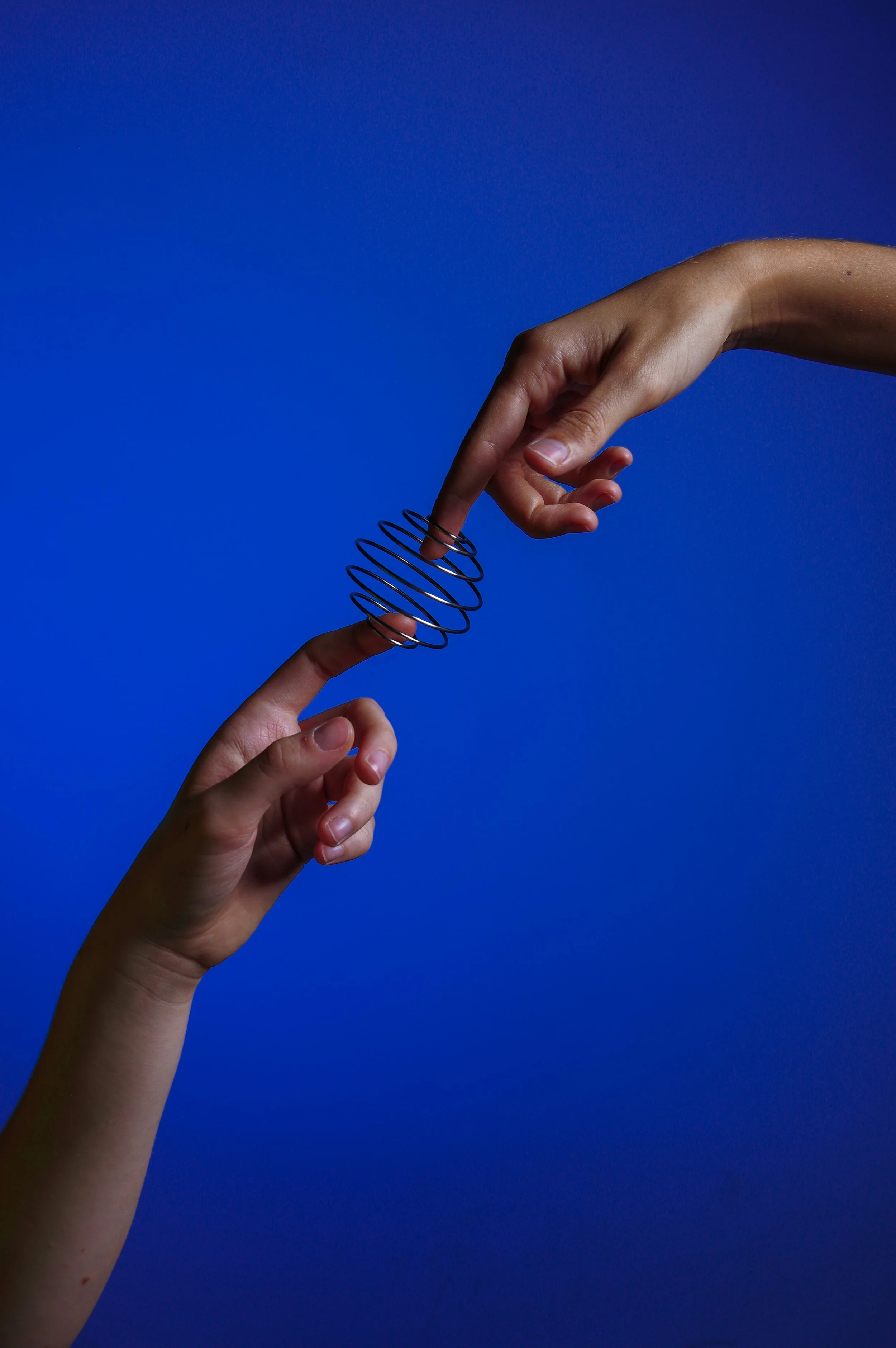

When we think about communication, we often focus on what we are trying to say to another person. But the act of producing language–whether writing or speaking–is only half of communication. Effective communication requires a reader or a listener. If you write something and no one ever reads it, the content is not communicated. If you say something but no one hears you, your message hasn’t been communicated. In other words, effective communication isn’t just what we produce, but also how well we listen.

So often, we practice the delivery of our message–public speaking, effective writing–but how often do we think about our role as readers or listeners? How often do we consider our skills at receiving messages? Not often enough.

For many people, the act of hearing is incredibly passive. We can close our eyes, but we can’t close our ears. Sound just comes in. It finds us. But we can choose what sounds we pay attention to, think about, attribute meaning to, or are bothered by. And that attention to sound, the meaning-making of sound, is really what listening is–paying attention to what we are hearing.

Want a more in-depth refresher on professional writing?

Try our Better Business Writing: On Demand course. This self-paced, virtual course will teach you strategies to become a more efficient and effective writer, and provide you with expert feedback

To be an effective listener requires us to pay attention to, focus on, and connect with another person. Barriers to effective listening include external distractions–phones, ambient noises, multiple humans talking at once–and internal ones–thinking about what we are going to say next or about what we are going to eat for dinner or about the person who cut us off on the highway this morning. There are lots of things inside our heads and outside our bodies vying for our attention. But when we are really trying to participate in effective communication, when we are working to listen, we have to concentrate on the other person in the present moment.

Steps to take to become a more effective listener include putting away and silencing the phone, finding a quiet space to have a conversation, or reminding people to speak one at a time and avoid interrupting. Internally, good listening requires us to focus on the other person. We should observe their body language–posture, gestures, eye contact–for nonverbal cues about their emotional state. We should arrange our own bodies to show that we are listening–uncrossed, open arms and legs, facing toward the person. We should acknowledge our internal state: I’m frustrated that person cut me off this morning, but I don’t need to think about that now; or I’m hungry so I’ll get a snack when we are done talking. And then remind ourselves that for the next 5 or 10 or 30 minutes we are going to give our full attention to what this other person has to say.

In practice, keeping our attention on the other person can be difficult. Especially when they are trying to say something difficult, uncomfortable, or emotionally involved. We often think that listening involves being silent, being passive, but listening is actually an active process. A good listener doesn’t have to remain silent, but does work to keep the focus of the conversation on that person. We can encourage the speaker to continue by asking questions (What happened next? Or How did you feel about that?). We can help the speaker process by reflecting back to them what we are hearing (It sounds like that bothered you. Or I think you are saying that you need more options. Is that accurate?). And we can also show we are listening with smaller encouragements (Totally! I agree. Ok. Mm-hmm.).

In Kate Murphy’s book, You’re Not Listening, she suggests that “When you leave a conversation, ask yourself, What did I just learn about that person? What was most concerning to that person today? How did that person feel about what we were talking about? If you can’t answer those questions, you probably need to work on your listening” (p. 68). That seems like a good practice to develop to check in on our listening skills after the fact and remind us what our goals should be as effective communicators–to gather information from other people as much as (more than?) sharing information ourselves.

Murphy’s book provides fascinating insights about how listening works from research on babies, couples therapy, biology, and social media. But if you think you might benefit from more specific exercises to improve your listening skills, Ximena Vengoechea’s book, Listen Like You Mean It, offers illustrations, exercises, reflections, and specific activities that can help you check your skills and figure out your own areas for improvement.

Active listening is a communication skill that requires practice, just like public speaking or writing emails, but honing this skill helps you communicate better and establishes your professionalism and credibility. You need to know some basics and then you have to do it over and over to keep learning how to apply those strategies. Give yourself opportunities to practice being the audience (receiver, listener, reader), too.