Persuasion: Imagining you are the *other* person

Jenny Morse, PhD

Author and CEO

Aristotle is to be blamed for teaching us the so-called “rhetorical triangle” of ethos (credibility), logos (logic), and pathos (emotion). Of course, the reason teachers are still teaching ethos, pathos, and logos is because we have centuries of testing that shows they work.

Your ability to persuade is determined by whether the audience can trust you, whether you can provide logical and relevant evidence, and whether the audience has an emotional stake in your content.

We won’t listen to people we don’t trust (ethos): credibility is the foundation for all effective communication.

But we also don’t listen to people who we don’t *care* about, or who don’t make us *feel* something (pathos). We want to feel connected or inspired or powerful; maybe we want to feel angry or sad. Whatever the emotion, persuasion will only work when we *feel* it.

And we think that we don’t listen to people who don’t make sense (logos). But we also know that every impassioned arguer has their own version of the facts and evidence. The information makes up the content of what you are saying, but, as Robert Sapolsky explored in his book Behave, the facts don’t matter as much as our feelings.

Want a more in-depth refresher on professional writing?

Try our Better Business Writing: On Demand course. This self-paced, virtual course will teach you strategies to become a more efficient and effective writer, and provide you with expert feedback

What this means for effective persuasion is that you have to tap into the audience’s perspective–what the other person cares about or wants or needs. You have to imagine living their life and having their experiences. What would make that person want what you’ve got? Or what would make that person do what you want them to do?

Too often, we focus on why *we* would do it or on the ways in which the product or service clearly improves people’s lives. But there are millions of useful products that have died from lack of an audience. And there are plenty of useless products that sell millions (Beanie Babies, anyone?)

Convincing people to buy something or do what you want them to do has more to do with capturing how they feel than with what they logically need.

To do this effectively, we, the persuaders, have to exercise something called theory of mind. Theory of Mind is a psychological concept that refers to the ability to imagine how another person is thinking or feeling. Humans start to develop this around the age of 3. One of my favorite experiments on this appears in Netflix’s documentary series Babies. A researcher sits across from a two year old sitting on their mother’s lap; a bowl of cookies and a bowl of broccoli are between them. The researcher starts saying how she wants broccoli. The two year old shoves the bowl of cookies across the table like “you don’t know what you want, lady.” Same experiment with a three year old. The researcher starts saying she wants broccoli, and the three year old, slowly, suspiciously, uncertain about the researcher’s dietary choices, passes the bowl of broccoli across the table. Amazingly, the three year old has just demonstrated theory of mind.

As we age, our ability to imagine other people’s perceptions increases and improves. The more people we know, the more we experience that other people’s thoughts, actions, feelings, and beliefs do not always overlap with our own 100%. And so we learn that there are lots of ways to think and feel and act and believe–even if our way is the best way.

When we want to get other people to do what we want them to do, giving them clear information and instructions will allow them to follow through. The content does matter. But they won’t even process the information or start step 1 of the instructions without a motivation to act.

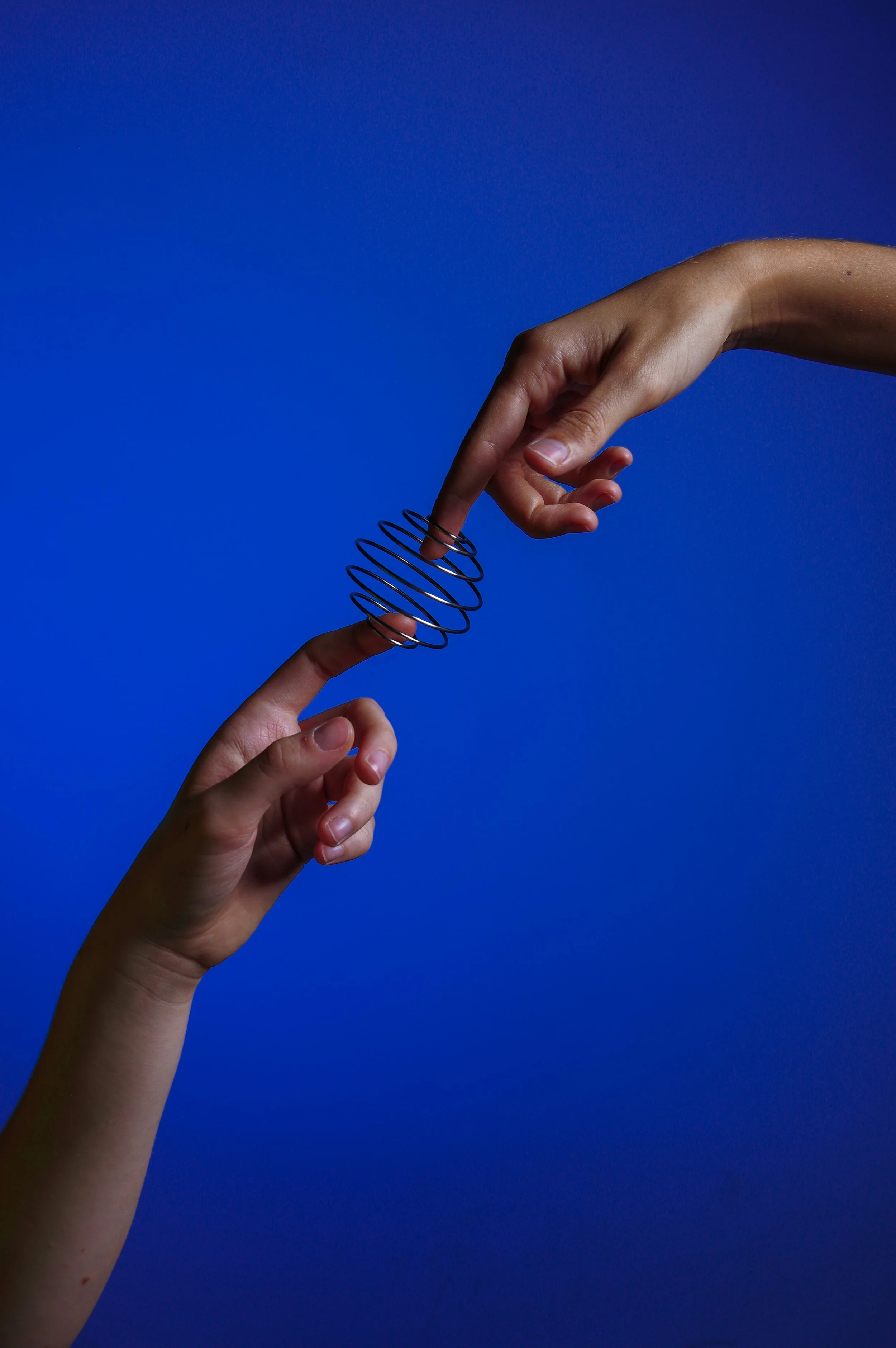

So how do we get them to…move? It’s probably not a coincidence that we use “move” to refer to both our actions and our feelings (I moved the box out of the way. That film moved me to tears.). All of our actions are predicated on a feeling (just ask Sapolsky).

We can imagine what would get us to move, but in most cases, we already know why our product or service or whatever is valuable. We know why it should be done or needs to be done, and we’ve already bought into that result.

The other person doesn’t know that. The other person has no information or basis on which to act–or at least not the same information to enable them to act.

Sometimes they will act because it is routine, or part of their job. Sometimes they will act because they have been trained to–my mom raised me to x. Sometimes because it is cultural–how many times have you smiled at someone politely even though you really didn’t feel like smiling?

But getting people to do something new and different requires them to feel the reason before they understand the reason.

For effective persuasion, start by imagining what the other person would feel. What do they feel before they get your message, purchase the product, and/or participate in the activity? What is their starting feeling? And what will your message, product, or activity change about their feelings? That change is what you are using to motivate the other person. Their current state is uncomfortable or wanting something in some way, and when they do what you want them to do, they will feel better.

When I worked in publishing, I had a very busy boss, always running around the office, who would never sign off on the stack of paperwork that sat in her inbox. She had to sign off on everything, but she found signing boring and stationary. The only way I could get her to sign off on all the documents was by going into her office, looking at the pile, and saying “Once they are all signed, I will leave.”

As soon as I walked into her office, she felt bothered, disturbed, interrupted. She didn’t like that I needed her to sit down and do a particular task. So, I promised her that once the stack was signed, she would be free. And it worked. Every day.

How can you apply theory of mind more effective persuasive messages? Easy. Persuasive messages start with the rationale (and that rationale has to tap into the other person’s emotions–wants, needs, and values) and then the ask.